This is What Wall Street Banks are Hiding in the Post-Election Euphoria

Here's why the Fed's own research could be showing hidden signs of financial black clouds on the horizon.

In the rush of post-election market euphoria, the biggest banks on Wall Street were among the winners.

The XLF ETF fund, which tracks the financial sector through the biggest financial firms, has risen for five straight months, reaching a high of $50 this week.

Much of that upside was attributed to the performance of the largest banks in the sector. Many of those large commercial banks have been getting even bigger by acquiring smaller ones – with several gobbling up community banks across small towns around the U.S.

The move is part of a growing trend that’s creating fewer banks. The biproduct of this trend is an even more concentrated financial industry. History shows us that this shift is also a recipe for risk.

Back in 2007 and early 2008, I wrote extensively on budding problems in the banking sector. The big banks were holding too many faltering subprime loans and what we now call toxic assets (if you want a primer, read my book, It Takes a Pillage.)

Sadly, no one listened then. Yet the top-heavy nature of the banking system was a major factor contributing to the 2008 financial crisis. Certain big banks were “too big to fail.” I'm not saying we’ll have a similar crisis; central banks stand too eager to step in with printing money – but that doesn’t mean clear skies either.

Today, the five largest U.S. banks (JPMorgan Chase, Bank of America, Wells Fargo, Citibank, and US Bank) hold combined assets of more than $10 trillion. That’s up from $6.8 trillion in 2014 and more than double the assets of the next largest 15 banks.

Meanwhile, their percentage of problem or non-performing loans (NPL) is rising. Below, we’ll unpack why that matters. But first, you should know what a practice called “extend and pretend” means on Wall Street.

Extend and Pretend

In a nutshell, it means that banks extend the maturity of a loan and pretend that the loan is healthier because it has more time for borrowers to pay it through smaller payments along the way.

There’s an accounting reason for this practice, too. Banks can set aside less capital for “healthy” loans. This means they can keep more capital on hand for other purposes – like trading and speculating.

Last month, the New York Fed released a paper called “Extend and Pretend in the U.S. CRE Market.” The research explains how Wall Street is using extend and pretend to make its commercial real estate (CRE) portfolios look better than they really are.

As the authors noted: “Banks with weaker marked-to-market capital – largely due to losses in their securities portfolio since 2022:Q1 – have extended the maturity of their impaired CRE mortgages coming due and pretended that such credit provision was not as distressed to avoid further depleting their capital.”

In English, that means banks turned today’s actual losses into tomorrow’s possible losses.

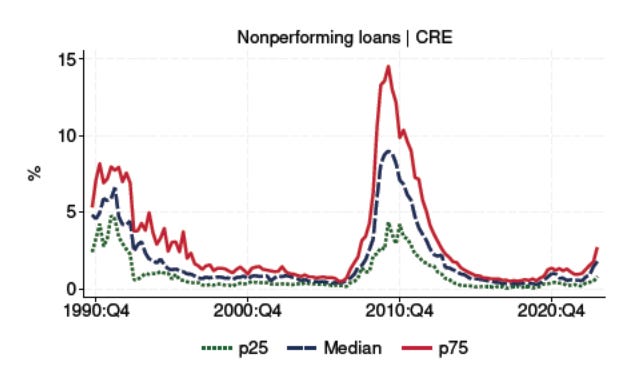

Non-performing loans are starting to inch back upward at the far right of the chart – and toward levels not seen since 2008. The chart below is signaling unsettling concerns that, despite all the big banks’ support right now in the markets, the numbers simply cannot hide.

The Maturity Wall

But there’s a reckoning to the “extend and pretend” practice – and there almost always is. It happens when bank loans crash into the “maturity wall.” That’s when the debt reaper shows up. That’s when the debt becomes due, its borrowers still can’t pay it, and then bank losses escalate quickly – often in a short time period.

The New York Fed’s researcher’s analysis found that “the maturity wall represents a sizable 16% of the aggregate CRE debt held by the banking sector.” The size of the CRE debt market is $5.9 trillion. So, we’re talking about a maturity wall of nearly a trillion dollars of potentially problem debt. That’s the size of the entire subprime loan market in 2008.

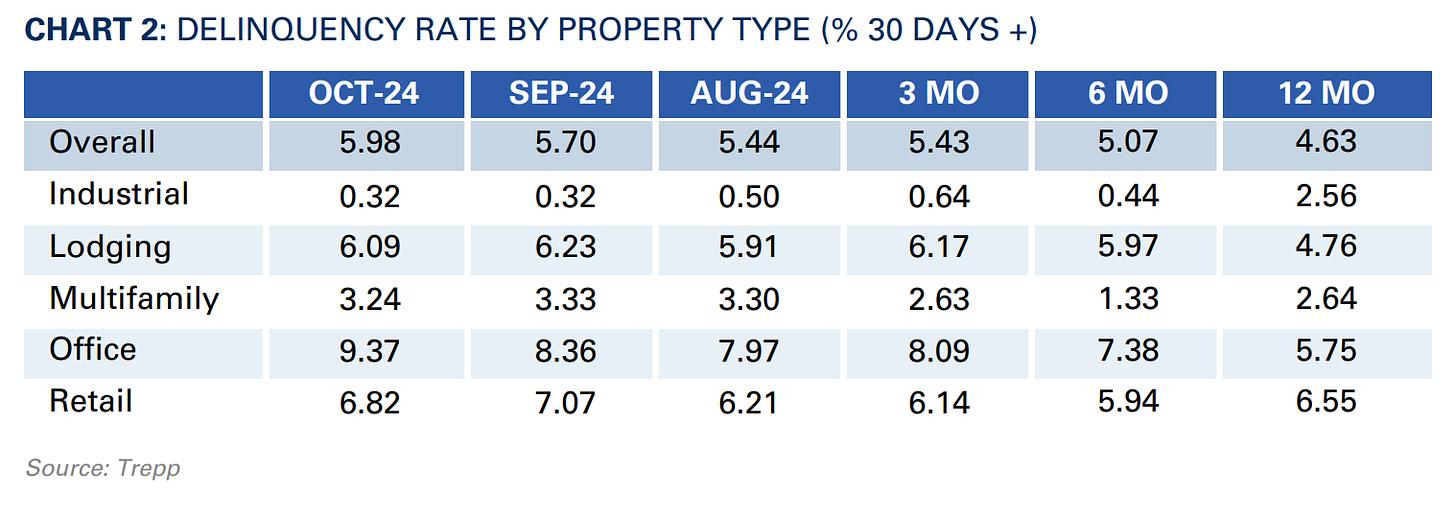

We are also facing a situation where “too big to fail” banks have gotten bigger – only this time, we are looking down the barrel of rising CRE loan losses. Highlighted by the chart below, delinquency rates on Commercial Mortgage-Backed Securities on properties overall have risen – with office properties accounting for over 9%.

Historically, we’ve seen a version of this movie before in the turmoil that led to the financial crisis of 2008. In 2008, the protagonist was subprime loans. This time around its commercial real estate loans.

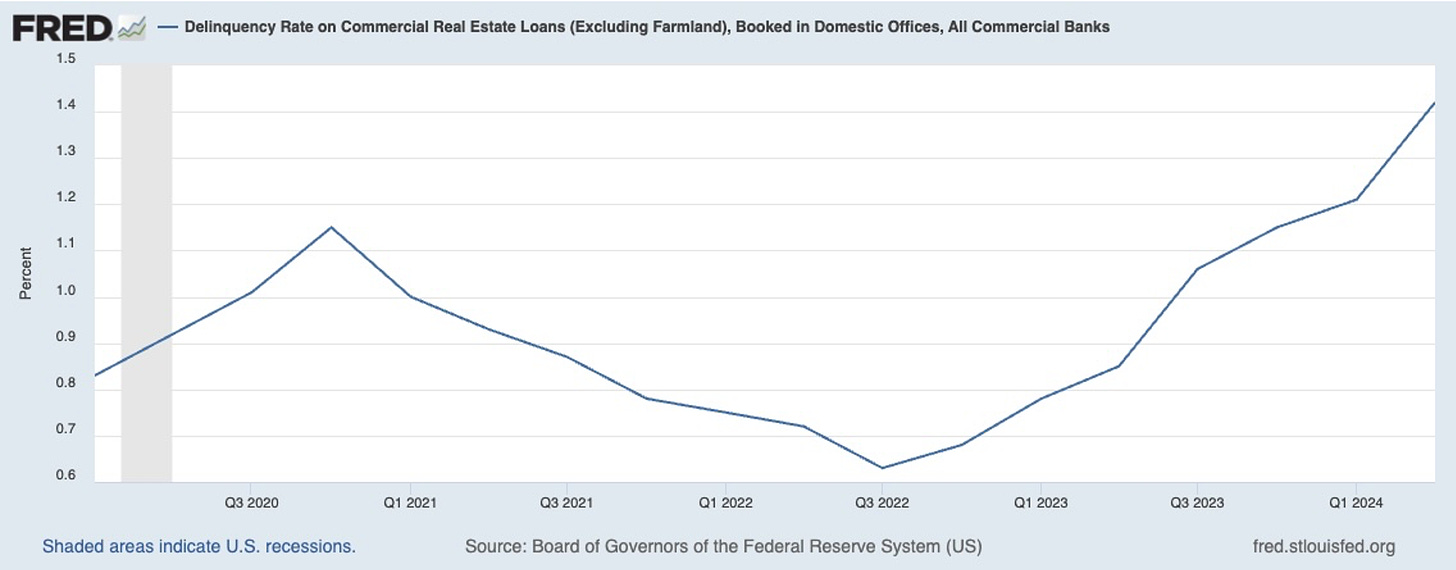

Of particular concern, as you can see below, is the fact that CRE delinquencies are rising quickly.

U.S. banks are sitting on $750 billion in unrealized losses on real estate securities.

Unusual Whales recently detailed, “Public filings and research indicate that 47 out of 1,027 American banks with assets over $1 billion have potential liabilities and losses exceeding 50% of their capital equity. These are still unrealized losses, meaning the banks holding these assets haven’t necessarily lost money yet, but they could if conditions worsen.”

The New York Fed's research paper admitted as much. It noted how “Banks 'extended-and-pretended' their impaired commercial real estate mortgages in the post-pandemic period” warning that the modifications could lead to “credit misallocation and a build-up of financial fragility.'"

That's why provisions, or the amount banks set aside to absorb loan losses, are growing. This past quarter, the four largest U.S. banks set aside $8.4 billion in loss provisions. That’s up from $5.7 billion in Q3 2023.

JPMorgan was the top dog in loss provisions. The Wall Street bank booked $3.1 billion in loss provisions in Q3 2024, more than double (up 124.8%) the same period a year ago. Loss provisions also grew at Citi and Bank of America. That increase was driven mainly by CRE losses.

Prinsights Premium readers, don’t miss our latest monthly issue that details two major utilities that are powering the energy transformation!

It may be that the bigger banks weather the CRE storm through “extend and pretend” methods. However, if the New York Fed itself is concerned, it signals that there might be stormy skies ahead.

For those considering alternatives to the biggest banks and financial volatility, one option to consider is to spread your money across multiple banks. That diversification offers a way to diffuse your risk that might escalate at any one bank.

You should also consider keeping an emergency fund of accessible cash outside of the banking system. While it sounds extreme, the move offers security in case something happens to your bank – allowing you to have your own reserve funds. If recent anomalies from the Silicon Valley Bridge Bank (SVB) to Signature Bank fiascos taught us anything at the end of 2022, it’s that having contingencies, even in the modern era, are worth consideration.

Great piece, Nomi! Very concerning...